There were some commercial radio stations broadcasting in Sweden from 1921, but from January 1st 1925, Radiotjänst AB (Radio Services Ltd) was awarded all broadcasting rights in Sweden by the Swedish government. The programming was financed through a radio (and TV) licence fee charged to all Swedish households who owned radio and/or television reception equipment. Since 2019 the licence fee has been replaced by a so called public service tax.

In 1955 the programs from Radiotjänst were split in two; Program 1 (P1) and Program 2 (P2). In 1957 Radiotjänst changed name to Sveriges Radio (Sweden’s Radio). In 1964 another station was created (P3) and in 1965 the stations were formated into P1 (talk), P2 (classical music and regional programs) and P3 (popular music). In 1987 a new fourth network (P4) took over regional programs from P2.

In 1978 the Swedish center-right government allowed for low power non-commercial open access station in certain areas as a trial, and in 1982 the Swedish parliament passed the Community Radio Act (SFS 1982:459). The programming was financed by the licence holders themselves, usually via membership fees, as commercial content were prohibited by law.

It wasn’t until the 1990-ies that commercial radio was allowed in Sweden again.

The Broadcasting Act of 1993

In 1993 the Swedish center-right government brought the Act on Local Radio Broadcasting (SFS 1993:120) to the Swedish parliament, who passed the act. The act stated that

- Local radio licences should be released by the Swedish Broadcasting Authority, for an eight-year period, with options of prolongation

- Any company or individual could apply for a licence, except newspapers

- Licences should be awarded to the highest bidder in a public auction

- The highest bid should also form the annual licence fee, indexed every year according to inflation

- The same licence holder can not hold more than one licence in any broadcasting area

- Should the licence holder not be able to pay the annual fee, the licence should be returned to the Swedish Broadcasting Authority and be re-released for a new public auction

- Licences can be re-sold to anyone, as except to newspapers or other licence holders in the same broadcasting area

- Regarding programming content, the only provision is that one third of the programming must be produced uniquely for the licence.

- Both local radio and community radio (public access) were allowed to finance their programming through commercials.

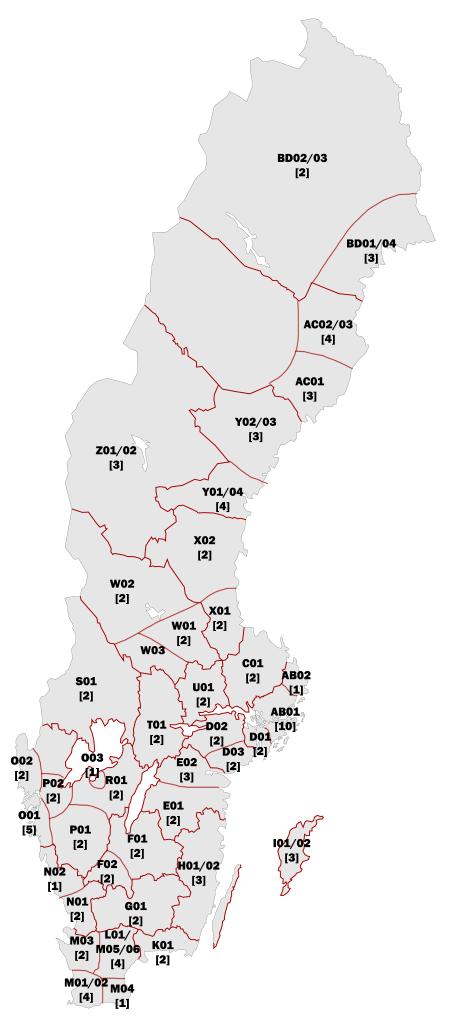

The Swedish Broadcasting Authority released approximately 80 licenses in around 40 broadcasting areas between 1993 and 1995. Broadcasting areas consisted of cities with 100 000 inhabitants and above. The authority released two licences to most areas, with the exception of 10 licences in Stockholm and 5 licences in Gothenburg.

At the auctions, it was clear that the market valued the licences highly, with typical fees around 1 million krona (€ 100 000) per year. Although there were a big variety of licence holders, it was soon clear that most licence holders only were fronts for a small number of local, national and international media companies, including a variety of newspapers formally excluded from the auctions. A majority of the licences were one way or another controlled by five private national media companies (MTG, Bonniers, SBS, NRJ Group and Fria Media). Shortly after the auctions, it also transpired that most independent owners were not able to pay the annual fees, and sold their licences to either of the five national media companies. Other independent owners retained their ownership of the licences, but gave either of the five national media companies the right to broadcast their formats on the licences instead.

Licences owned by, or whos programming was delivered by, the private national broadcasting companies mostly sent national programming, meeting the provision of one third of the programming content should be unique to the licence with a ”local” music mix eight hours every night. In some broadcasting areas, both licence holders were either controlled by the same company or the programming contents was produced by the same company.

Both practices (local nightly music mixes and ownership/programming concentration) were appealed against to the supervising body the Swedish Broadcasting Commission, but were upheld as to be according to the letter (if not spirit) of the Local Radio Broadcasting Act.

The Broadcasting Act of 2001

In 1994, the new center-left government of Sweden tried to amend the Broadcasting Act with a provision to stop any new public auctions until the parliament had passed a new Broadcasting Act with a new method to award new licences. The provisions were not passed until 1995, and then all auctions were halted.

The center-left government intended to replace the public auctions with a jury awarding broadcasting licences to the ”best” bidder for a fixed annual fee of 40 000 krona (€ 4 000). However, this approach met with resistance from both supervisory bodies and the parliament, and it wasn’t until 2001 when the parliament passed a new Broadcasting Act (SFS 2001:272).

The new Broadcasting Act of 2001 stated that:

- Any licence holder could retain their licence with the provisions of the former Broadcasting Act, including the annual fee set by the public auctions of 1993-1995

- There should be no changes to the provisions of broadcasting areas and ownerships

- Any new licence should be awarded to the bidder who promised to broadcast the highest proportion of unique programming content to the licence

- Current licence holders or applicants controlled by any current licence holder in the broadcasting area in question should not be able to be awarded any new licence.

Only a few number of broadcasting licences were released after the act, but of those were awarded, the new act presented a new set of problems.

Although strong provisions against ownership concentration in broadcasting areas, media companies were able to circumvent the provisions with formally indepentent companies who won the bids, but commissioned an existing licence holder to provide the new licence with programming content.

The biggest problem however arose when judging what ”unique content” meant. Broadcasting licences were awarded to applicants who promised to broadcast most unique content. But when the licence holders failed to meet their promises, all the Swedish Broadcasting Commission could do was to give the licence holders fines. The fines were conciderably smaller than the annual fees holders of licences awarded according to the Broadcasting Act of 1993 had to pay.

Although the new act gave the Broadcasting Authority the possibility to withdraw the licence from holders who didn’t meet their own promises of unique programming content, this possibility was concidered a breach of the Basic Law on Freedom of Expression, since the withdrawal according to the Broadcasting Act of 2001 were based on the (lack of unique) programming content of the licence holder.

This was in conctrast to the possibility of withdrawal according to the Broadcasting Act of 1993, which was based on the ability to pay the fee (and not content, therefore not applicable to the Basic Law on Freedom of Expression).

The new method of awarding broadcasting licences with a jury to the applicant who promised most unique programming content was eventually concidered a failure by both center-left and center-right parties in the parliament.

During the this period the ownership structure was further centralised with only MTG, SBS and NRJ as the remaining owners of licences and with MTG and SBS providing virtually all content programming to all broadcasting licences.

The Broadcasting Act of 2010

In 2010 the parliament passed a new Broadcasting Act (SFS 2010:606), proposed by the center-right government, but supported by the center-left opposition.

The new Broadcasting Act of 2010 stated that:

- The provisions of unique content of both the 1993 and 2001 Broadcasting Acts were abolished.

- Also community radio (public access) was excempt from having to provide unique programming content.

- All current holders of licences could retain their licences according to the provisions of either act, but only until 2018.

- Any new licence should be awarded to the highest bidder in a closed bidding contest. The bid should be final and paid up front, but without any annual fee. All new licences should also expire in 2018.

At the end of the period there were 103 licences in 39 broadcasting areas. Of the 103 broadcasting licences, the programming contents of 73 licences were provided by Bauer Media (formerly SBS) with 5 different formats, 29 by MTG (currently called Viaplay Group) with 5 different formats, with only one remaining independent programming content provider.

Of the 103 licences, 21 were awarded according to the 2010 broadcasting act (closed bidding contest), 8 according to the 2001 broadcasting act (jury) and 74 by the 1993 broadcasting act (public auction).

New broadcasting areas and auctions of 2018

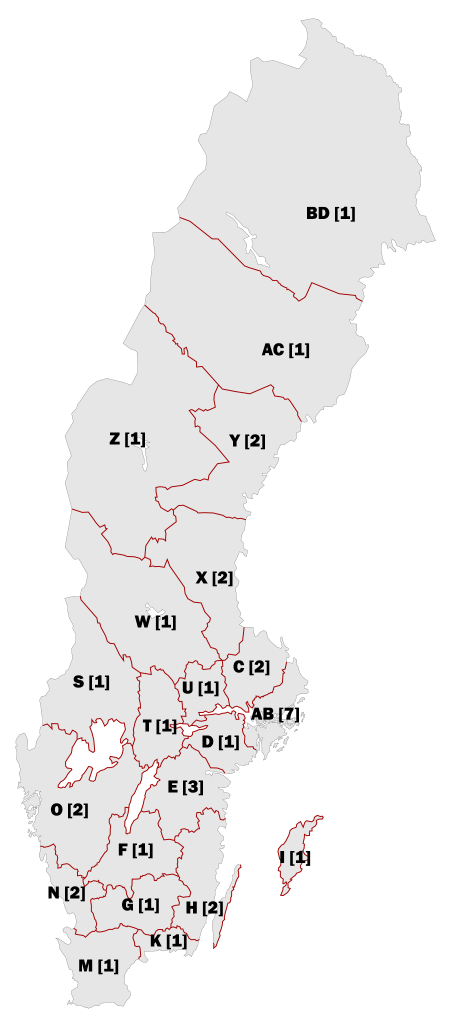

After deciding not to replace FM with DAB broadcasting in 2015, the new center-left government commissioned the Swedish Broadcasting Authority to construct new FM-broadcasting areas, and the Swedish Post and Telecom Authority to find as many FM-frequencies as possible to a new release of broadcasting licences in 2018 for a new eight year period. The Telecom Authority assigned frequencies to four national packages, with additional frequencies in some areas.

The Broadcasting Authority decided to allocate the first three frequency packages to three national networks and the remaining frequencies to 35 licences in 21 local broadcasting areas (corresponding to Sweden’s 21 counties). The government also instructed the Broadcasting Authority to hold a stricter view on ownership and programming concentration in individual broadcasting areas.

The new broadcasting licences were released in 2017, and the three national broadcasting licences were awarded to Bauer Media, NRJ Group and MTG (currently called Viaplay Group), who paid between 200 million and 400 million krona (€ 20 000 000-40 000 000) for each licence. Of the remaining 35 local licences, MTG/Viaplay won 17, Bauer Media won 8 and NRJ Group won one. The remaining 9 local licences were awarded to a further four companies.

Already when applying for licences, NRJ stated that they would cooperate with Bauer Media on the sale of commercials, but not on the programming content, as did some of the independent applicants of local licences. This was however judged by the Broadcasting Authority to meet the new stricter standards against ownership and programming concentration, when the authority awarded the licences.

National licences

- National 1: Mix Megapol (owned and operated by Bauer Media)

- National 2: NRJ (owned and operated by NRJ Group)

- National 3: RIX FM (owned and operated by Viaplay Group)

Local licenses

- Star FM (owned and operated by Viaplay Group): 18 out of 21 areas

- Rockklassiker (owned and operated by Bauer Media): 6 areas

- Rockklassiker (co-owned by Bauer Media and Mad Men Media and operated by Bauer Media) 2 areas (Stockholm and Västra Götaland)

- Bandit (owned by NTM and operated by Viaplay Group): 2 areas (Stockholm and Uppsala)

- Vinyl (owned by Vinyl Group and operated by Bauer Media): 2 areas (Stockholm and Östergötland)

- Lugna favoriter (owned by DB Media and operated by Viaplay Group): 1 area (Stockholm)

- Radio Nostalgi (owned and operated by NRJ Group): 1 area (Stockholm)

- Feel Good Hits (owned and operated by Bauer Media): 1 area (Stockholm)

- Retro FM (co-owned by Bauer Media and Mad Men Media, operated by Mad Men Media): 1 area (Skåne)

Plans for 2026

In 2024, the centre-right government suggested revisions to the Broadcasting Act of 2010, to be in force by the next eight year period 2026-2034. The suggested revisions are:

- Every applicant must pay a registration fee of 45 000 SEK (4 500 EUR)

- Replace the closed bidding contest with a new ”beauty contest”, where the Broadcasting Authority awards each license according to the following criterias:

- A variety of formats, for both national and local licenses

- Mutually independent ownership of the different license holders

(These are the same as the current criterias for awarding DAB-licenses)

- The Broadcasting Authority must judge that the applying license holder has both financial and technical abilities to uphold broadcasting during the entire eight year period.

- The future license holders must still pay an annual fee, corresponding to 3 % of the overall commercial radio business’ annual income. The total fee will be dispersed to individual licenses according to system to be decided by the Broadcasting Authority.

This is an example of how the fee system could look like:

- Class 1: 18 % of the total fee (3 national licenses only)

- Class 2: 3.6 % of the total fee (10 licenses in Stockholm, Västra Götaland and Skåne counties)

- Class 3: 0.55 % of the total fee (10 licenses in the 6 largest counties, except those mentioned above)

- Class 4: 0.3 % of the total fee (15 licenses in the remaining 12 counties)

(The total annual fee is expected to be around 30 million SEK (3 million EUR), compared to the 160 million SEK (16 million EUR) under the current system)

The main reasons for the suggested revisions are:

- All license holders think that the current fees are too high, and that the fees stops the development of commercial radio

- The closed bidding contests has resulted in very varying fees to technically equal licenses. For example, national licenses has been awarded to bids varying from 200 million SEK to 400 million SEK (20 million EUR to 40 million EUR), and the licenses in Stockholm has been awarded to bids varying from 8 million SEK to 38 million SEK (800 000 EUR to 3.8 million EUR), thus contributing to unequal competetion between the individual license holders.

- Analogue broadcasting frequencies is however a limited natural resource where the demand still exceeds the supply. Therefore an annual fee is still warranted.